It seems that, every year, there's an ongoing debate about the Ravens' front seven: Do they play a 3-4 or a 4-3? Are they switching to one or the other in the off-season? And how will that affect their defensive philosophy?

After all, the Ravens made their name as an attacking, opportunistic defense. They've intimidated quarterbacks and stifled running backs for most of their 18-year history, and fans take pride in the defensive tradition in Baltimore.

So with that in mind, I dug into the defensive front that the Ravens will use as their "base" this season: the 4-3 Under.

Showing posts with label Playbook. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Playbook. Show all posts

Monday, August 4, 2014

Friday, August 1, 2014

Running Back "Vision" in the Zone Blocking Scheme

Much has been made about Gary Kubiak bringing his brand of the West Coast Offense to Baltimore for the 2014 season.

In order for Kubiak's system to work effectively, the run game must be efficient. But what makes a good running back in Kubiak's zone blocking scheme? And what is meant by running back "vision"? I decided to take a deeper dive into the rushing attack that the Ravens will rely on this season.

In a previous post, I broke down the blocking rules for the zone blocking scheme, but I didn't touch heavily on the role of the running back. Despite what many might think, there's more to being an effective zone rushing back than possessing the "one-cut-and-go" buzz-phrase that always gets thrown around. Running backs have strict reads that are temporally tied to the blocks of the offensive lineman in front of him.

In order for Kubiak's system to work effectively, the run game must be efficient. But what makes a good running back in Kubiak's zone blocking scheme? And what is meant by running back "vision"? I decided to take a deeper dive into the rushing attack that the Ravens will rely on this season.

In a previous post, I broke down the blocking rules for the zone blocking scheme, but I didn't touch heavily on the role of the running back. Despite what many might think, there's more to being an effective zone rushing back than possessing the "one-cut-and-go" buzz-phrase that always gets thrown around. Running backs have strict reads that are temporally tied to the blocks of the offensive lineman in front of him.

Thursday, July 31, 2014

Playbook: Power O

Power O is possibly the most ubiquitous running play in football history. It is popular at every level of the game, mostly because it works. For example, below you'll see a screen cap of the Ravens using Power O last season. But if you click link #7 in Outside Resources, you'll also see a PowerPoint presentation from a high school coach who installed Power O as his base run play. It's that widely used.

In this play, each lineman down blocks (seals off the back side) while the backside guard pulls to the play side and attacks the SAM linebacker. It's a demanding assignment for the guard, who needs to be quick-footed and athletic to get around to the play side and then attack the linebacker in space. Some offenses also use a fullback as a lead blocker to kick out the end man on the line of scrimmage (E; below). Finally, to make Power O work, teams need a back who can explode through the hole with timing and the ability to cut off of his blocks.

Here's a look at it on the chalkboard:

When it all comes together, Power O has a number of advantages. It's good against a variety of defensive looks, it can be used on multiple downs and distances, and it's great for setting up high-percentage play action passes later in the game. The Ravens even used it from the shotgun at times, as in the play below:

Like its name implies, Power O is just good, old-fashioned power football. No misdirection, just smart blocking and patient running.

Outside Resources

1) Explanation and Cut-ups of the "Power O" Run Play

2) Want to Learn the Base NFL Run Game?

3) NFL 101: Introducing the Power Running Game

4) The Coach's Corner: Utilizing New Power-O Innovations in the Spread Offense

5) The "Power O" Play

6) Playbook: Wisconsin's 'Power O' Scheme

7) Power "O"

8) One Back Power Game: Separating the Defense

9) More "Bang" for your Buck with the Power Scheme

10) Football Fundamentals: Power O Blocking Primer

11) Football Fundamentals: Power O Blocking (Part II)

12) POWER Variations Series

13) Power Variations #2 - Super Power

14) Power Variations #3 - 1 Back Power

15) Power Variations #4 - Power Arc

16) Football Fundamentals: RB and HB Blocking

17) Football Fundamentals: The Many Iterations of Power O

In this play, each lineman down blocks (seals off the back side) while the backside guard pulls to the play side and attacks the SAM linebacker. It's a demanding assignment for the guard, who needs to be quick-footed and athletic to get around to the play side and then attack the linebacker in space. Some offenses also use a fullback as a lead blocker to kick out the end man on the line of scrimmage (E; below). Finally, to make Power O work, teams need a back who can explode through the hole with timing and the ability to cut off of his blocks.

Here's a look at it on the chalkboard:

When it all comes together, Power O has a number of advantages. It's good against a variety of defensive looks, it can be used on multiple downs and distances, and it's great for setting up high-percentage play action passes later in the game. The Ravens even used it from the shotgun at times, as in the play below:

Like its name implies, Power O is just good, old-fashioned power football. No misdirection, just smart blocking and patient running.

Outside Resources

1) Explanation and Cut-ups of the "Power O" Run Play

2) Want to Learn the Base NFL Run Game?

3) NFL 101: Introducing the Power Running Game

4) The Coach's Corner: Utilizing New Power-O Innovations in the Spread Offense

5) The "Power O" Play

6) Playbook: Wisconsin's 'Power O' Scheme

7) Power "O"

8) One Back Power Game: Separating the Defense

9) More "Bang" for your Buck with the Power Scheme

10) Football Fundamentals: Power O Blocking Primer

11) Football Fundamentals: Power O Blocking (Part II)

12) POWER Variations Series

13) Power Variations #2 - Super Power

14) Power Variations #3 - 1 Back Power

15) Power Variations #4 - Power Arc

16) Football Fundamentals: RB and HB Blocking

17) Football Fundamentals: The Many Iterations of Power O

Playbook: Lead

Lead, or lead draw, is one of the most recognizable running plays in football. There are many variations, including HB Lead, FB Lead, Lead Strong, Lead Weak (or Open), etc., but all are meant to be quick-hitting running plays.

The blocking is man, meaning every OL, TE, and RB will have an assignment. This is a basic play that requires no "window dressing," as Matt Bowen puts it. The offense simply lines up and executes, leaving it up to the linebacker to be quick enough to fill the gap.

Here's another example. The play below is FB Lead Strong. FB Vonta Leach is the lead blocker (hence the name) through the 2-hole. Leach, along with C Gradkowski and LT Monroe, will take on the linebackers while the other linemen block out. RB Bernard Pierce will look for a quick opening and take the ball right up the middle. With the right blocking, this play will effectively gain solid yardage, though it's unlikely to go for a big gain.

1) Playbook Sessions: The Base NFL Run Game

2) Want to Learn the Base NFL Run Game?

3) NFL 101: Introducing the Power Running Game

4) Football Fundamentals: Iso Primer

5) Football Fundamentals: RB and HB Blocking

The blocking is man, meaning every OL, TE, and RB will have an assignment. This is a basic play that requires no "window dressing," as Matt Bowen puts it. The offense simply lines up and executes, leaving it up to the linebacker to be quick enough to fill the gap.

Here's another example. The play below is FB Lead Strong. FB Vonta Leach is the lead blocker (hence the name) through the 2-hole. Leach, along with C Gradkowski and LT Monroe, will take on the linebackers while the other linemen block out. RB Bernard Pierce will look for a quick opening and take the ball right up the middle. With the right blocking, this play will effectively gain solid yardage, though it's unlikely to go for a big gain.

Outside Resources

1) Playbook Sessions: The Base NFL Run Game

2) Want to Learn the Base NFL Run Game?

3) NFL 101: Introducing the Power Running Game

4) Football Fundamentals: Iso Primer

5) Football Fundamentals: RB and HB Blocking

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Playbook: Wham

"Wham" is a counter to standard gap or zone rushing plays that generally utilizes an inside trap element from a full- or H-back.

Often times the "wham" will come against a nose-tackle (as above). The center (Birk) uses an "olay" block (ignores the man aligned over him, climbs to second level) allowing Leach to trap the nose tackle. It is an effective way to occupy a 2-gapping defensive lineman with one player instead of double-teaming him.

The success of this playcall tends to arise from its unpredictability. Defensive lineman who have seen wham on tape are taught to collision the wham-blocker creating an undesirable amount of traffic at the point of attack. However, a play-action compliment to this play can also be effective.

FB Vonta Leach (#44) with a "wham" block on NT Casey Hampton

Often times the "wham" will come against a nose-tackle (as above). The center (Birk) uses an "olay" block (ignores the man aligned over him, climbs to second level) allowing Leach to trap the nose tackle. It is an effective way to occupy a 2-gapping defensive lineman with one player instead of double-teaming him.

|

| A draw-up of an H-back Wham on a 1-technique DT. Courtesy of Coach McElvany |

The success of this playcall tends to arise from its unpredictability. Defensive lineman who have seen wham on tape are taught to collision the wham-blocker creating an undesirable amount of traffic at the point of attack. However, a play-action compliment to this play can also be effective.

|

| A variant of Wham that uses play-action to get the H-Back into the flat |

Outside Resources:

- Complimenting the Inside Zone with Wham

- What is a Wham Block?

- Playbook Session: The Base NFL Run Game

- Draw Up: The 49ers and the Wham Play

- Film Study | Because We All Need A Little More WHAM in Our Lives

- All 22 film breakdown: How the 49ers found their offensive identity versus the Rams

- A Multiple Run Game with the Zone Scheme

- Film Review: OSU Tight Zone Wham vs. Oregon

Labels:

Playbook

Sunday, July 27, 2014

Playbook: Inside Trap

Generally speaking, traps are quick-hitting runs meant to gain a few tough yards.

Traps compliment plays like the Zone Read and Power O to achieve a well-rounded ground game. And anyone on the offensive line can run a trap: one OL leaves his man intentionally unblocked, only to be picked up by a different lineman - often unseen by the defender.

The inside trap asks one guard (in the image below, LG A.Q. Shipley) to leave his man intentionally unblocked and move immediately to the second level. The other guard (below, RG Marshall Yanda) "trap" blocks, or comes around behind the center and takes on the defender vacated by the first guard.

The rest of the line tries to block out - away from the middle of the field - to give the running back as much space as possible.

Outside References

Thursday, July 24, 2014

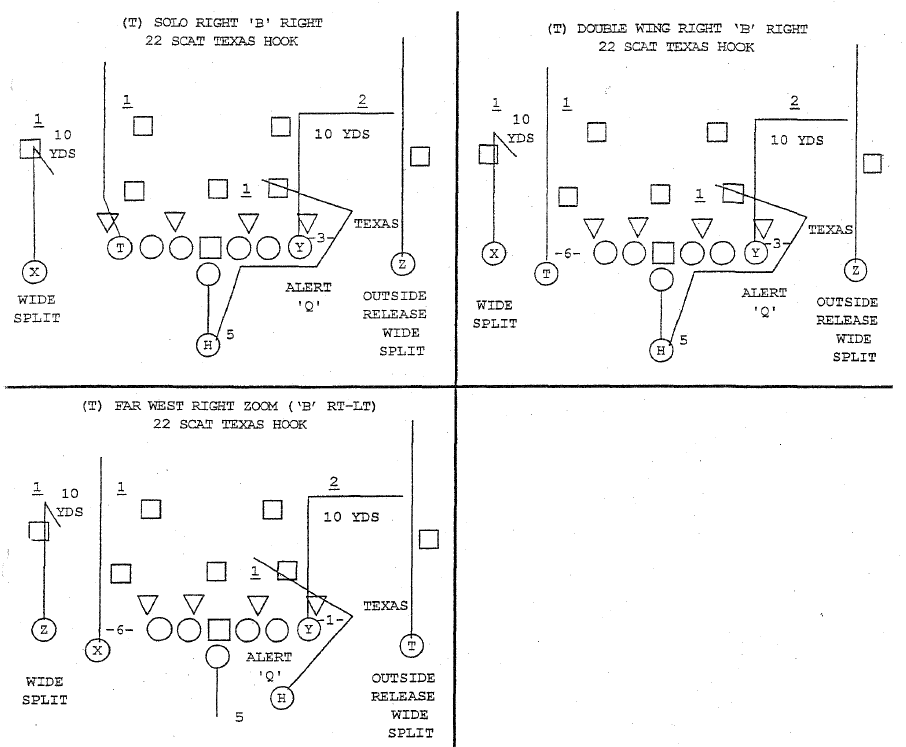

Playbook: Texas

"Texas" is a route, usually from a running back out of the backfield that is defined as "run 1 yard outside [tight end], plant outside foot on [line of scrimmage], break at a 45 [degree] angle. Cross [linebacker's] face, keep going vs. man or zone" via the 2004 Shanahan playbook. Texas is also considered a playcall with specific complementary routes from proximal receivers.

In order to isolate a slower middle linebacker on a running back in the middle of the field, the slot receiver above takes the nickel back out of the play by running an "out." The Texas route initially pulls the linebacker toward the sideline and the inside cut forces the linebacker to trail the running back. Its a flexible route combination vs. man and zone but works best against man coverage.

1) The "jerk" route and "follow" concept from bunch

2) All-22: Film Study on how the Ravens rebounded against the Giants

3) The TEXAS concept in the West Coast Offense

4) Texas Passing Concept

5) The Texas Concept: Using Your RBs in Base Routes

In order to isolate a slower middle linebacker on a running back in the middle of the field, the slot receiver above takes the nickel back out of the play by running an "out." The Texas route initially pulls the linebacker toward the sideline and the inside cut forces the linebacker to trail the running back. Its a flexible route combination vs. man and zone but works best against man coverage.

Via the Shanahan playbook, the running back uses a "Scat" (i.e. free) release and is commonly the first read in the quarterback's progression.

The 2012 Ravens combined the Drive concept with the Texas route, a combination referred to as "Follow"

Ray Rice (orange) has a fantastic match-up versus a linebacker in the middle of the field. With Dennis pitta running the underneath "drive" route, Rice follow him and use the vacated middle of the field to pick up yards after the catch.

Alternate terminology for the Texas route includes 'angle.'

Outside References

2) All-22: Film Study on how the Ravens rebounded against the Giants

3) The TEXAS concept in the West Coast Offense

4) Texas Passing Concept

5) The Texas Concept: Using Your RBs in Base Routes

Labels:

Playbook

Playbook: Spot

"Spot" is a three receiver route combination that is found in every NFL playbook. It is run out of a three receiver side (backs and tight ends included) and consists of a corner route, a flexible intermediate route (curl,whip, in), and a flat route.

This combination places pressure on a number of defensive looks. There is a horizontal and vertical stretch component that makes this sequence of routes so lethal.

To a defense that hasn't strictly prepared for this playcall, the proximity of the routes can cause hesitation in the defensive back's judgement. For example, a "cloud" or rolled up corner back (as in the Cover-2 scheme) can easily get "Hi-Lo'ed" by the flat and curl routes where a hook defender (W, above) can be stretched laterally.

Often times the reads for the quarterback go from 1) corner, to 2) curl, to 3) flat. Although this changes based on defensive scheme and field position.

1) Snag, stick, and the importance of triangles (yes, triangles) in the passing game

2) Three routes you must stop to win in the NFL

3) An inside look at the Packers' 'Spot Route'

4) Coach Maisonet's Spot Route Concept

5) Simplifying Passing Concepts

6) Brady and Manning All-22: Spot Passing Concept

7) Snag Route: Noel Mazzone

8) Detroit Lions All-22 Breakdown: Pistol Spot Passing Concept

9) Snag and Scat Revisited

10) A look at the 'X Spot'

11) All-22: Snag, Tempo and the Eagles

This combination places pressure on a number of defensive looks. There is a horizontal and vertical stretch component that makes this sequence of routes so lethal.

To a defense that hasn't strictly prepared for this playcall, the proximity of the routes can cause hesitation in the defensive back's judgement. For example, a "cloud" or rolled up corner back (as in the Cover-2 scheme) can easily get "Hi-Lo'ed" by the flat and curl routes where a hook defender (W, above) can be stretched laterally.

Often times the reads for the quarterback go from 1) corner, to 2) curl, to 3) flat. Although this changes based on defensive scheme and field position.

"Spot" is a fantastic call in the redzone. It floods zone defenses to one side or can utilize a "pick" element against teams using man coverage.

Alternate terminology for Spot includes "Snag."

Outside References

2) Three routes you must stop to win in the NFL

3) An inside look at the Packers' 'Spot Route'

4) Coach Maisonet's Spot Route Concept

5) Simplifying Passing Concepts

6) Brady and Manning All-22: Spot Passing Concept

7) Snag Route: Noel Mazzone

8) Detroit Lions All-22 Breakdown: Pistol Spot Passing Concept

9) Snag and Scat Revisited

10) A look at the 'X Spot'

11) All-22: Snag, Tempo and the Eagles

Labels:

Playbook

Playbook: Counter

Counter is one of the staple "power" running plays at every level of football. The back fakes one direction after the snap but then takes the handoff the opposite direction, following a pulling guard through the hole. The guard will either kick out the end man on the line of scrimmage or lead the back through the designed hole, depending on the defensive front:

The counter is designed to trick the defense, which often keys on a running back's first step. If the first step is a false one, the defense will begin flowing to the wrong side of the field. Any hesitation or misdirection in the defense is a win for the offense.

In the play below, RG Marshall Yanda is pulling, and RB Ray Rice will follow him through the hole.

In the play below, RG Marshall Yanda is pulling, and RB Ray Rice will follow him through the hole.

Outside References

Sunday, July 20, 2014

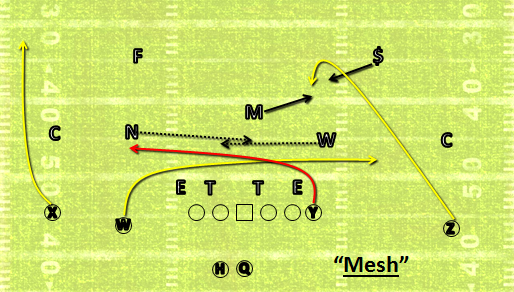

Playbook: Mesh

Mesh is a common pass play in a number of systems. It involves two opposite inside receivers crossing paths forming a natural pick against man coverage.

1) Better Know A Pass Pay - Mesh

2) Air Raid Playbook - The Mesh

3) Texas Tech Air Raid - Pass Play 92 (Mesh)

4) Jets 92 Mesh

5) Mesh Play, Shallow Package - A Simple Yet Devastating Attack

6) Mesh Variations

7) Valdosta State Air Attack

8) The shallow cross, drag, and drive in the west coast and spread offenses

9) Oregon vs Michigan State Preview: Ducks Vertical Passing Game

10) Rethinking "MESH"

One receiver is designated as crossing over the other while the opposite receiver runs underneath of his route. The "traffic" that is caused by multiple defenders and receivers gives the quarterback defined reads after the receivers break to the opposite side of the field.

Against man coverage, the two defenders are forced to chase from behind and are likely to get picked or rubbed while chasing.

The "mesh" terminology is common in the Air Raid playbook, but the play exists in the West Coast Playbook as well. Against zone coverage, the receivers read where the defender's areas begin and end, and sit in between them.

Outside References

2) Air Raid Playbook - The Mesh

3) Texas Tech Air Raid - Pass Play 92 (Mesh)

4) Jets 92 Mesh

5) Mesh Play, Shallow Package - A Simple Yet Devastating Attack

6) Mesh Variations

7) Valdosta State Air Attack

8) The shallow cross, drag, and drive in the west coast and spread offenses

9) Oregon vs Michigan State Preview: Ducks Vertical Passing Game

10) Rethinking "MESH"

Labels:

Playbook

Playbook: Flanker Drive

Flanker Drive (or "Z Drive") is a West Coast staple where the typical strong-side wide receiver ("Z") runs a "drive" or "shallow" route that progresses all the way to the opposite side of the field.

The drive route (red) is designed to remain shallow throughout the play while a 10-12 yard dig route (yellow) forms behind it by the in-line tight end. The weak-side receiver ("X" or split end) generally occupies the cornerback to make space for the drive route which will reach a depth of 4-6 yards by the time it reaches the far numbers.

Flanker drive puts stress on the middle linebacker (M) as he needs to choose whether to drop to cover the tight end or to collapse onto the drive route. With good rapport between QB and receiver, the drive and dig routes will sit in between zones and get up-field immediately upon catching the ball. On the weak side, the X and W will occupy the corner, nickelback and free safety.

Against man coverage, the drive route will run away from the corner assigned to him. With the corner on his back, the Z receiver can catch the ball in full stride.

The QB's reads will depend on the perceived coverage, but the reads are often drive, to dig, to check-down (running back swing). Variants of this play can place the drive route on the opposite side of the tight end drag (Hi-Lo Opposite) or use double drive routes from opposite sides of the field (Mesh) that creates a natural pick.

1) St. Louis Rams Shallow Cross Concept

2) Georgia Bulldogs Passing Concept (Shallow, Y-Corner)

3) Play Diagram - Flanker drive explained

4) The shallow cross, drag, and drive in the west coast and spread offenses

5) West Coast Offense Playbook: Brown Right F Short 2 Jet Flanker Drive

6) Classic WCO play - Flanker drive

7) Lions vs Packers All-22 Drive Concept

8) The Pass Concept that Changed My Life

9) West Coast Offense.pdf

The drive route (red) is designed to remain shallow throughout the play while a 10-12 yard dig route (yellow) forms behind it by the in-line tight end. The weak-side receiver ("X" or split end) generally occupies the cornerback to make space for the drive route which will reach a depth of 4-6 yards by the time it reaches the far numbers.

Flanker drive puts stress on the middle linebacker (M) as he needs to choose whether to drop to cover the tight end or to collapse onto the drive route. With good rapport between QB and receiver, the drive and dig routes will sit in between zones and get up-field immediately upon catching the ball. On the weak side, the X and W will occupy the corner, nickelback and free safety.

Against man coverage, the drive route will run away from the corner assigned to him. With the corner on his back, the Z receiver can catch the ball in full stride.

The QB's reads will depend on the perceived coverage, but the reads are often drive, to dig, to check-down (running back swing). Variants of this play can place the drive route on the opposite side of the tight end drag (Hi-Lo Opposite) or use double drive routes from opposite sides of the field (Mesh) that creates a natural pick.

Outside References

1) St. Louis Rams Shallow Cross Concept

2) Georgia Bulldogs Passing Concept (Shallow, Y-Corner)

3) Play Diagram - Flanker drive explained

4) The shallow cross, drag, and drive in the west coast and spread offenses

5) West Coast Offense Playbook: Brown Right F Short 2 Jet Flanker Drive

6) Classic WCO play - Flanker drive

7) Lions vs Packers All-22 Drive Concept

8) The Pass Concept that Changed My Life

9) West Coast Offense.pdf

Labels:

Playbook

Sunday, July 13, 2014

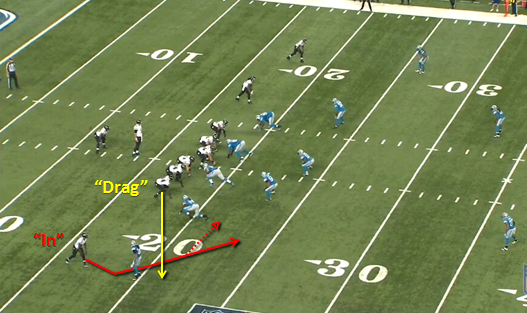

Playbook: Dragon

Dragon is a quick hitting West Coast route combination where the quarterback gets the ball out after 3 steps. The term "dragon" comes from the tight end's "drag" route and the #1 (outside) receiver's "in" (i.e. slant route).

The tight end's "drag" route is defined as "drag 3-5 yards, if no ball sit 3 yards from sideline" (via the Shanahan 2004 playbook). The tight end "drag" route should not be confused with a "drive" or "cross" that has also been referred to as "drag."

The outsider receiver runs a quick three yard vertical stem and breaks at a 45 degree angle inside. He can convert this slant to an "in" if a zone dropper occupies his original destination:

The primary read is the drag. The secondary read goes to the slant/in and the half-back (H; above) acts as the third/checkdown read.

A slight variant of "dragon" asks the outsider receiver to make his initial break at 5-8 yards (called "Drag Slant").

Outside References

1) West Coast Offense

2) Pass Concepts

3) Josh McDaniels and the Slant-Flat Concept in Superbowl XLIX

The tight end's "drag" route is defined as "drag 3-5 yards, if no ball sit 3 yards from sideline" (via the Shanahan 2004 playbook). The tight end "drag" route should not be confused with a "drive" or "cross" that has also been referred to as "drag."

The outsider receiver runs a quick three yard vertical stem and breaks at a 45 degree angle inside. He can convert this slant to an "in" if a zone dropper occupies his original destination:

The primary read is the drag. The secondary read goes to the slant/in and the half-back (H; above) acts as the third/checkdown read.

A slight variant of "dragon" asks the outsider receiver to make his initial break at 5-8 yards (called "Drag Slant").

Outside References

2) Pass Concepts

3) Josh McDaniels and the Slant-Flat Concept in Superbowl XLIX

Labels:

Playbook

Playbook: 2-Man

A common way to play man coverage in the NFL is use two deep-half safeties with the underneath defenders playing "trail man" technique.

The deep safeties will drop to the top of the field numbers as their landmark. Here they will drive toward deep and/or out-breaking routes. The underneath coverage defenders use a "trail man" tactic where they will sit on the inside hip of their assigned receiver and break on any inside breaking routes. This trail position forces difficult throws to vertical routes between the man defender and collapsing safety. Cornerbacks have the option to play press coverage as they have help over the top.

2) 3-4 Cover 2 Man Under Defense

3) Understanding coverages and attacking them with the passing game

4) 4-3 Cover 2 Man

5) NFL 101: Breaking Down the Basics of 2-Man coverage

The deep safeties will drop to the top of the field numbers as their landmark. Here they will drive toward deep and/or out-breaking routes. The underneath coverage defenders use a "trail man" tactic where they will sit on the inside hip of their assigned receiver and break on any inside breaking routes. This trail position forces difficult throws to vertical routes between the man defender and collapsing safety. Cornerbacks have the option to play press coverage as they have help over the top.

Outside References

1) Film Session: Packers '2-Man' vs. the Bears2) 3-4 Cover 2 Man Under Defense

3) Understanding coverages and attacking them with the passing game

4) 4-3 Cover 2 Man

5) NFL 101: Breaking Down the Basics of 2-Man coverage

Labels:

Playbook

Playbook: Tare

"Tare" is a short yardage route combination from a "trips" (i.e. 3 receiver side) alignment consisting of a 9-route by the outside receiver, a quick out/flat by the #2 receiver, and a "stick" or "option" route by the innermost receiver:

The outermost receiver (#1) takes an outside release to lift the cornerback from the flat area. The 9-route here will rarely be thrown to; it is meant to clear the defender. The #2 receiver takes a quick release to the flat and takes his coverage assignment with him. The primary read is #3 who runs the "stick" route. Often times the #3 receiver to one side can force a mismatch with a linebacker or a strong-safety. Versus man coverage, a bursting out-cut at 3-4 yards forces the defender to chase from the inside out. Versus zone coverage, the #3 receiver can sit between two zones and catch the ball for short yardage.

A variant of this combination can stretch the defense vertically by releasing the "flat" route with no depth (quick flat) and running the "stick" combination between 5-8 yards. This forces underneath zone defenders to declare which receiver they will cover based on their depth.

2) How did Stafford, Calvin Johnson beat the Raiders?

3) NFL 101: Introducing the Basic Red-Zone Combinations

4) NFL Preseason 2013: Takeaways and Key Plays from Week 3

The outermost receiver (#1) takes an outside release to lift the cornerback from the flat area. The 9-route here will rarely be thrown to; it is meant to clear the defender. The #2 receiver takes a quick release to the flat and takes his coverage assignment with him. The primary read is #3 who runs the "stick" route. Often times the #3 receiver to one side can force a mismatch with a linebacker or a strong-safety. Versus man coverage, a bursting out-cut at 3-4 yards forces the defender to chase from the inside out. Versus zone coverage, the #3 receiver can sit between two zones and catch the ball for short yardage.

A variant of this combination can stretch the defense vertically by releasing the "flat" route with no depth (quick flat) and running the "stick" combination between 5-8 yards. This forces underneath zone defenders to declare which receiver they will cover based on their depth.

Outside References

1) Breaking Down Woodson versus the 'Tare' route2) How did Stafford, Calvin Johnson beat the Raiders?

3) NFL 101: Introducing the Basic Red-Zone Combinations

4) NFL Preseason 2013: Takeaways and Key Plays from Week 3

Labels:

Playbook

Thursday, July 3, 2014

Playbook: Route Trees

Both the Ravens' old system, the Air Coryell, and their new one, Kubiak's version of the West Coast offense, use numbered route trees to denote the various routes that receivers will run.

The trees vary slightly from team to team, but generally speaking, even numbered routes break inside and odd numbered routes break toward the sideline.

Here's a look at the West Coast route tree:

This image shows typical routes for both the X and Z receivers. The numbered routes also have commons names:

0: Hook

1: Flat

2: Slant

3: Out

4: Curl

5: Hitch

6: Dig or In

7: Flag

8: Post

9: Go

The Air Coryell route tree looks similar, if a little more basic:

Here, you see the similarities (and the differences) between the Coryell and the West Coast systems. With more intermediate and horizontal routes, the West Coast offense tries to stretch the field horizontally more-so than vertically, like the Coryell system does.

Outside Resources:

1) West Coast Offense

2) The Spread Multiple West Coast Offense

3) Saints Football 101: Receivers, Routes, and Personnel

The trees vary slightly from team to team, but generally speaking, even numbered routes break inside and odd numbered routes break toward the sideline.

Here's a look at the West Coast route tree:

This image shows typical routes for both the X and Z receivers. The numbered routes also have commons names:

0: Hook

1: Flat

2: Slant

3: Out

4: Curl

5: Hitch

6: Dig or In

7: Flag

8: Post

9: Go

The Air Coryell route tree looks similar, if a little more basic:

Here, you see the similarities (and the differences) between the Coryell and the West Coast systems. With more intermediate and horizontal routes, the West Coast offense tries to stretch the field horizontally more-so than vertically, like the Coryell system does.

Outside Resources:

1) West Coast Offense

2) The Spread Multiple West Coast Offense

3) Saints Football 101: Receivers, Routes, and Personnel

Sunday, June 22, 2014

Playbook: Smash

"Smash" is a very common two man route combination consisting of a short inward breaking route (or hitch) by #1 and a corner route (aka "flag", "7") by #2:

The "Smash" combination provides a "rub" element for the #1 receiver underneath while working to "Hi-Low" a "cloud" corner in Cover-2:

| ||

| Ray Rice (#1; yellow) runs a shallow "in" route while slot receiver Marlon Brown (#2; red) runs a corner route |

Against Cover-2, the corner playing the Smash combo is in a bind. The #1 receiver is running through this corner's short zone but jumping the "in" route leaves the deep half safety chasing the corner route (red) from his inside landmark. Coaches and quarterbacks refer to this bind as "High-Lowing" a corner. Its the reasoning why Smash is still a standard Cover-2 beater at all levels.

To effectively play this combination as a corner, he must recognize that #1 is breaking shallow, pass him off to the hook/curl player (N/Nickel in the above image), and sink to "cushion" the corner route to give the quarterback a smaller window.

A variant on this playcall is the "smash switch" or "China" which refers to the outside receiver running the corner route and the inside player sitting in the flat.

Outside References

Labels:

Playbook

Saturday, June 21, 2014

Playbook: Cover-6

Cover-6 is a relatively common term for a "Quarter-Quarter-Half" zone defense. This playcall combines Cover-2 to one side and Cover-4 to the other, forming an asymmetric look for the opposing quarterback:

2) Coach's Corner: Split Coverages in Football

3) Football's One-Gap 3-4 Defense

4) Understanding coverages and attacking them with the pass game

5) cover 6

6) Loaded Zone

On the weak side of the formation (bottom of the image), the corner is playing man coverage if #1 attacks vertically (>8 yards). If #1 breaks in or out prior to 8 yards, the corner will sink to his deep quarter of the field and prepare for any deep out-breaking routes from #2. The weak-side safety plays with standard Cover-4 rules where he plays man coverage on #2 vertical or doubles #1 if #2 breaks short.

On the strong side of the field (top of the image), the defense is playing with standard Cover-2 zone rules. The safety is responsible for a deep half of the field and the corner is playing his flat responsibility. A corner at this depth is referred to as a "cloud" corner and is often used to high/low bracket a threatening receiver (e.g. Calvin Johnson, above). This corner is taught to funnel the receiver to the inside at the snap to minimize the void between himself at the half-field safety. He will then turn his eyes to the quarterback and jump any short/flat routes.

The strong-side linebacker plays his hook/curl zone while the weak-side linebacker and slot defender play hook/curl and flat zones, respectively.

Cover-6 is an easily disguised coverage as it can be veiled as a number of coverages prior to the snap. The 2013 Baltimore Ravens were particularly fond of this playcall and periodically played Cover-4 on one side and 2-Man on the opposite.

Outside References

3) Football's One-Gap 3-4 Defense

4) Understanding coverages and attacking them with the pass game

5) cover 6

6) Loaded Zone

Labels:

Playbook

Thursday, June 19, 2014

Playbook: Cover-4

Cover-4 (or "Quarters") is a four-deep, three-under zone defense but plays out with man principles. Although there are four deep players, they do not need to cover a great deal of ground and can therefore play closer to the line of scrimmage. Closer safeties means Cover-4 is a sufficient run defense.

The cornerbacks generally line up >7 yards off the widest (#1) receivers and play man coverage if they attack vertically further than 8 yards. If #1 releases underneath or runs a quick out-breaking route, the corner must gain depth and play a deep 1/4 zone.

The safeties in Cover-4 read the #2 receiver (can be a slot receiver, TE, or RB). If #2 releases vertically, the safety is in man coverage. If #2 breaks his route prior to 8 yards, the safety doubles #1 from the inside. Safeties in Cover-4 often have run-game responsibilities as well, either "force" (i.e. set the edge) or cutback.

The underneath players in Cover-4 have a great deal of ground to cover. The two outside defenders defend any route into the flats while the middle player plays the middle hook and "walls off" any route underneath. The flats are a weakness of Cover-4 because slower players have a lot of ground to cover.

1) Inside the Playbook: Michigan State's Cover-4 Defense

2) NFL 101: Introducing the Basics of Cover

3) Read Call - Backside Safety Support

4) How Troy Polamalu and Ed Reed Changed NFL Defenses

5) Get Back to Fundamentals: Coverages

6) Breaking down the top Cover 4 beater

7) Playbook: Broncos' Cover 4 beater vs. the Saints

8) Film Room: AFC Divisional Round

9) The Quarters Coverage Study

10) Quarters Coverage

11) Press Quarters Coverage

12) 3 Insights to Improve Quarters Coverage

13) Quarters Coverage Alignments

14) Stanford Quarters Coverage vs. Oregon

15) Inside the Playbook: Cover 4 Safety Play

16) Quarters Coverage from Football-Defense.com

17) Quarters Coverage versus Pro Set, Twins, and Trips

18) Quarters Box Concept Versus Bunch Formations

The cornerbacks generally line up >7 yards off the widest (#1) receivers and play man coverage if they attack vertically further than 8 yards. If #1 releases underneath or runs a quick out-breaking route, the corner must gain depth and play a deep 1/4 zone.

The safeties in Cover-4 read the #2 receiver (can be a slot receiver, TE, or RB). If #2 releases vertically, the safety is in man coverage. If #2 breaks his route prior to 8 yards, the safety doubles #1 from the inside. Safeties in Cover-4 often have run-game responsibilities as well, either "force" (i.e. set the edge) or cutback.

The underneath players in Cover-4 have a great deal of ground to cover. The two outside defenders defend any route into the flats while the middle player plays the middle hook and "walls off" any route underneath. The flats are a weakness of Cover-4 because slower players have a lot of ground to cover.

Outside References

1) Inside the Playbook: Michigan State's Cover-4 Defense

2) NFL 101: Introducing the Basics of Cover

3) Read Call - Backside Safety Support

4) How Troy Polamalu and Ed Reed Changed NFL Defenses

5) Get Back to Fundamentals: Coverages

6) Breaking down the top Cover 4 beater

7) Playbook: Broncos' Cover 4 beater vs. the Saints

8) Film Room: AFC Divisional Round

9) The Quarters Coverage Study

10) Quarters Coverage

11) Press Quarters Coverage

12) 3 Insights to Improve Quarters Coverage

13) Quarters Coverage Alignments

14) Stanford Quarters Coverage vs. Oregon

15) Inside the Playbook: Cover 4 Safety Play

16) Quarters Coverage from Football-Defense.com

17) Quarters Coverage versus Pro Set, Twins, and Trips

18) Quarters Box Concept Versus Bunch Formations

Labels:

Playbook

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

Playbook: Cover 3

Cover 3 is one of the most ubiquitous and basic defenses in football, and it's popular from high school through the NFL. Matt Bowen calls it a "first-day install defense" for nearly any team.

At its most basic, Cover 3 has three deep zones and four underneath zones. The three deep zones are occupied by the free safety (who occupies the middle third) and the two outside corners (who drop into their respective thirds).

Underneath, the strong safety ($) and the open-side linebacker (W) will occupy the two curl/flat zones while the remaining linebackers sink into the two hook zones in the middle. Dropping the extra safety close to the line of scrimmage gives the defense an 8-man box allowing Cover 3 to be a base run defense. The basic Cover 3 looks something like this:

The curl/flat defenders (as shown above, the WILL and the strong safety) drop to the numbers and disrupt the curl route or break on the flat route.

Finally, the middle hook defenders drop to just outside the hash marks. They're tasked with protecting the seam and breaking on underneath crossing routes.

You'll notice that the above image is labeled Cover 3-Sky. The "S" in Sky identifies the force/contain player (the strong safety), just as the "B" in Cover 3-Buzz ('backer) and the "C" in Cover 3-Cloud (cornerback).

Cover 3-Buzz

Below, you can see Pittsburgh's defense in Cover 3-Buzz. Here, the force player is a linebacker rather than the strong safety. The strong safety (Polamalu) is dropping into a hook, and both outside linebackers are responsible for the curl/flat zones (at the top and bottom of the image).

Cover 3-Cloud

In this variation, the cornerback is the force/contain player. In the image below, the Ravens are showing 3-Cloud, and the strong safety is taking one of the deep third zones (bottom of the image). Below him, the corner stays in the curl/flat. One final difference: The hook defenders now must also help with curl responsibility if there's a receiving threat present.

1) NFL 101: Introducing the Basics of Cover 3

2) Stopping the run with a Cover-3 base defense

3) How Earl Thomas and the Seahawks' defense use the Cover 3

4) The Second Level: What You Need to Know Heading into Super Bowl XLVIII

5) Defensive Back Techniques: Cover 3 Pattern Read Examples

6) Film Study: Kaepernick vs. The Patriots

7) How do you beat Cover 3?

8) The Tape Never Lies: Breaking down the Cover 3

9) Cover 3 Alabama 2008 Cutups

10) Monte Kiffin: 3 Deep Coverage

11) Film room takeaways from the 2013-2014 season

At its most basic, Cover 3 has three deep zones and four underneath zones. The three deep zones are occupied by the free safety (who occupies the middle third) and the two outside corners (who drop into their respective thirds).

Underneath, the strong safety ($) and the open-side linebacker (W) will occupy the two curl/flat zones while the remaining linebackers sink into the two hook zones in the middle. Dropping the extra safety close to the line of scrimmage gives the defense an 8-man box allowing Cover 3 to be a base run defense. The basic Cover 3 looks something like this:

The free safety takes a deep drop and looks to break on the post or dig route or help over the top of an outside 9 route.

The corners, meanwhile, typically use one of two alignments: a soft cushion at the snap (shown above), or a "press-bail" technique, where they line up as if they're going to press the receiver but then "bail" at the snap to create a cushion. Either way, the corners are tasked with covering the receivers vertically and funneling deep, inside-breaking routes to the free safety.

Finally, the middle hook defenders drop to just outside the hash marks. They're tasked with protecting the seam and breaking on underneath crossing routes.

You'll notice that the above image is labeled Cover 3-Sky. The "S" in Sky identifies the force/contain player (the strong safety), just as the "B" in Cover 3-Buzz ('backer) and the "C" in Cover 3-Cloud (cornerback).

Cover 3-Buzz

Below, you can see Pittsburgh's defense in Cover 3-Buzz. Here, the force player is a linebacker rather than the strong safety. The strong safety (Polamalu) is dropping into a hook, and both outside linebackers are responsible for the curl/flat zones (at the top and bottom of the image).

Cover 3-Cloud

In this variation, the cornerback is the force/contain player. In the image below, the Ravens are showing 3-Cloud, and the strong safety is taking one of the deep third zones (bottom of the image). Below him, the corner stays in the curl/flat. One final difference: The hook defenders now must also help with curl responsibility if there's a receiving threat present.

Outside References

2) Stopping the run with a Cover-3 base defense

3) How Earl Thomas and the Seahawks' defense use the Cover 3

4) The Second Level: What You Need to Know Heading into Super Bowl XLVIII

5) Defensive Back Techniques: Cover 3 Pattern Read Examples

6) Film Study: Kaepernick vs. The Patriots

7) How do you beat Cover 3?

8) The Tape Never Lies: Breaking down the Cover 3

9) Cover 3 Alabama 2008 Cutups

10) Monte Kiffin: 3 Deep Coverage

11) Film room takeaways from the 2013-2014 season

Saturday, June 14, 2014

Playbook: Half Slide Protection

A common protection call which combines "area" (slide, zone) and "man" (BOB) schemes. As the name suggests, half slide protection asks one side of the offensive line (usually 3, sometimes 4, lineman) to block one adjacent gap in unison as in Full Slide protection. The other side of the line (usually including the running back) blocks players rather than zones, as in BOB protection.

9) A bit on our Combo man/slide protection

10) Universal Pass Protection Schemes that Sustain Multiple Movements and Pressures

11) Twists and slants: How to generate pressure with only 4 rushers

12) Football Fundamentals: Pass Protection Schemes

The above play shows the left tackle, left guard, and center all sliding to block their outside gaps. Since they are blocking "areas", they can protect against stunts/twists more efficiently and can give help to a lineman with a bad match-up. The other side of the line (right guard, right tackle, running back) are all blocking specific defenders. Running back Ray Rice is responsible for one of two linebackers if one of them should blitz. If both blitz to the man side, Flacco will need to get the ball out to a "hot" receiver (likely over the middle, in the space vacated by the rushing 'backer).

Half slide protection is popular because a linebacker is less likely to blitz than a down lineman, giving the running back a greater chance to release into a pattern. Half slide also allows the running back to follow a play-action path without losing sight of his blocking assignment(s).

Outside References

10) Universal Pass Protection Schemes that Sustain Multiple Movements and Pressures

11) Twists and slants: How to generate pressure with only 4 rushers

12) Football Fundamentals: Pass Protection Schemes

Labels:

Playbook

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)